This invention is a dance (a giga in fact), and as such is lively and bouncy. Youcan hear similar gigues on the French Suites in Eb and G.

You want to play it fast, but not so fast that you miss the accents (as discussed below) – somewhere around dotted crochet = 120. So I suggest playing it staccato throughout (or detached). (By the way, this rule of playing 8th notes detached and 16th notes legato is just superstition. The decision to play whatever legato and staccato must be taken on musical grounds, not because of some “rule”).

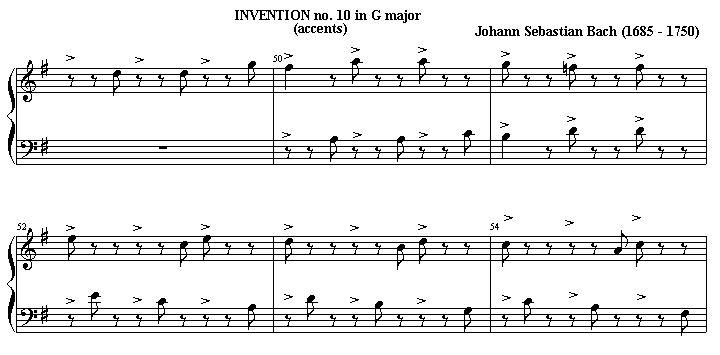

Now if you look at the score of this invention, the first thing striking about it is its uniformity of both rhythm and melody. The whole piece is basically made up of quavers in both hands. Compared to the rhythmic variety of the other inventions this one seems very dull and mechanical. Then most of it is made of arpeggios. Since Bach is one of the most inventive composers in the Baroque, and since this is a pedagogical piece (teaching one not only technique but above all composition and counterpoint), can it possibly be another level to this piece?

You bet. This piece is all about

accents. Bach kept all other musical components as simple as possible so that he could then instruct us on the art of using accents.

I am going to show you the first six bars, and let you have fun figuring out the rest of the piece.

First the time signature is 9/8, which is compound time, and therefore follows a 3/4 pattern, with each beat corresponding to a dotted crochet. In the score below, I have marked each beat with the symbol “>”. So you have a

metric pattern of accents. This is the first level. Every first note of the groups of three quavers is accented (the first one in each bar being a strong beat, and the other two weak beats).

Now here is what Bach does (and clearly had enormous fun doing it).

Because a note in the high register is naturally accented, Bach places the high notes at odds with the metric accent. I have marked the high notes in each group of three quavers by making the head of the note white:

Now, start by having a look at bar 3. There you can see that in both right and left hand the melodic accent (white notes) coincides with the metric accent (>)

Now have a look at bar 1 (I have enclosed in a rectangle the pair of descending arpeggios because – if you do a motif analysis of this piece – they are part of three out of the four motifs and because out of all the possibilities, Bach uses only three in this piece – numbered 1, 2 and 3). As you can see the melodic accents are now displaced in relation to the metric accent. This will actually be the case in all bars in the picture, except for bar 3.

Now, if you have a look at bar 2, you can see that in the right hand the melodic and metric accents coincide, but in the left hand, the melodic accent is displaced by two semiquavers. This is

accent counterpoint – the major feature in this invention. (Showing you that counterpoint needs not be melodic, but can also be harmonic and rhythmic).

You can see this accent counterpoint in most of the bars (look at the figures enclosed in the rectangles), but the best way to

hear it is to isolate the melodic accented notes (that is the highest notes in each group of three quavers).

The phrasing in this invention (as pretty much everything else) will be completely dependent on understanding the accent patterns (both metric and melodic) and how they interact.

Interestingly enough you need not worry about physically stressing this or that note. If you just play the piece as written, all this will come out naturally. So this is not a matter of physical work, but rather mental. You must hear the accent pattern in your mind. If you do that the fingers will naturally comply. Unfortunately no one can hear in one’s mind what one has not heard physically beforehand. So this is how you go about it.

1. Create a score where only the melodically accented notes are present. (As I have done for the first six bars above).

2. Now play this score (if you used a good notation software to create the score is even better, since you can then just listen to the midi associated with it) as many times as needed to completely memorise

what it sounds like.

3. Now listen to as many CDs of this piece as you can, and see in how many of the interpretations you can actually hear the pattern above. This will immediately tell you who are the good Bach interpreters and the ones who do not have a clue. (And your idea of making each three quavers a phrase is also not good, since it will completely destroy the accent pattern).

4. Now start working on the piece using the accent pattern as your guide towards tempo, phrasing, agogics, dynamics and other interpretative decisions. Anything that further the accent pattern is correct, anything that destroys it is incorrect.

5. Finally, on the matter of ornamentation, you can ignore all the mordents if you wish (they were not originally there – they were added by Bach later, much later), but not the trills.

Best wishes,

Bernhard.