Bringing Florence Price Back to Life: An Inside Look with Pianist Han Chen

A new recording of Florence Price’s Piano Concerto shines new light on the pioneering composer’s legacy. In this interview, Piano Street talks to pianist Han Chen, who reflects on Price’s fusion of Romantic and African American idioms, and the personal journey of interpreting her music for modern audiences.

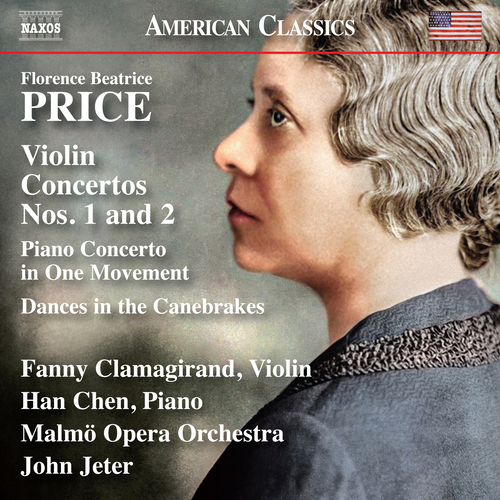

Pianist Han Chen can be heard on a recent recording of Florence Price’s “Piano Concerto in One Movement”, featured on Naxos, conducted by John Jeter with the Malmö Opera Orchestra. Chen’s interpretation is instrumental in reviving and honoring the legacy of Florence Price, now described as one of the early 20th century’s most influential African American composers. Chen’s expressive playing and emotional engagement have helped shed new light on Price’s significant yet overlooked contributions to American art music.

Florence Price, primarily celebrated as a pioneering composer, also displayed notable talent as a pianist. Having undergone rigorous organ and piano studies at New England Conservatory in Boston, she performed as a concert pianist early in her career. Her extensive training fostered a deep understanding of musical structure and expression – elements she masterfully integrated into her compositions. Price composed more than 300 works, including four symphonies, four concertos, as well as choral works, art songs, chamber music, and pieces for solo instruments. In 2009, a significant collection of her compositions and papers was discovered in her abandoned summer home, shedding new light on her prolific and important career.

This feature is available for Gold members of pianostreet.com

Play album >>

Some might remember Piano Street’s conversation with Han Chen on his recordings of Ligeti in 2024, and therefor it’s very pleasing to have him back on another interesting project. In this interview, Chen shares his experience of recording the Piano Concerto in One Movement. He talks about what drew him to Price’s music, how he approached a rediscovered work that mixes African American musical roots with classical traditions.

Chen’s engagement is a serious effort to bring Price’s unique voice back to life in concert halls.

Patrick Jovell: What made you want to record Florence Price’s Piano Concerto, given its history and importance in music?

Han Chen: I was first invited to participate in this project by Naxos Records, my long-time collaborator. Conductor John Jeter has released three albums of Price’s symphonic works on Naxos American Classics, and this new release continues that survey. At the time, I had read about the rediscovery of Price’s music in The New Yorker, but I had not yet heard her Piano Concerto. I looked it up online and listened to a few excellent recordings. My first impression was that it’s virtuosic, exuberant, and deeply touching. This concerto reflects Price’s continued effort to bring African American musical idioms into classical forms. In the resurgence of her music, we are also re-evaluating the historical importance of her and her contemporaries’ work. Music history has long favored boundary-pushing styles, but we are now at a moment of rethinking how significance is assigned. As a pianist who engages with both traditional and avant-garde repertoire, I’m deeply interested in filling the neglected spaces—both musically and personally. I was thrilled to be part of this project and to contribute to American music for the first time as a recording artist, especially since I have studied and worked primarily in the United States. In addition to the Piano Concerto in One Movement, this album also includes her two Violin Concertos (featuring violinist Fanny Clamagirand) and William Grant Still’s orchestration of her piano piece Dances in the Canebrakes, all recorded with the Malmö Opera Orchestra.

PJ: How did you handle interpreting a work that was long lost and recently reconstructed?

HC: For many decades, only a piano reduction of this concerto was available. Composer Trevor Weston reconstructed the orchestration in 2010 based on that reduction and Price’s notes. However, since 2020, her original orchestration has been published by G. Schirmer, and that’s the version we recorded. I didn’t approach it differently from how I would interpret a score by Bach or Beethoven. Price herself was an avid performer—on both piano and organ—and her music merits the same meticulous attention as old masters. I studied the score, read about her life, listened to recordings, and immersed myself in the work until I formed my own interpretation. Ultimately, a genuine interpretation must come from the heart.

PJ: Can you share your thoughts on the blending of European Romanticism with African American spiritual and dance traditions in this concerto?

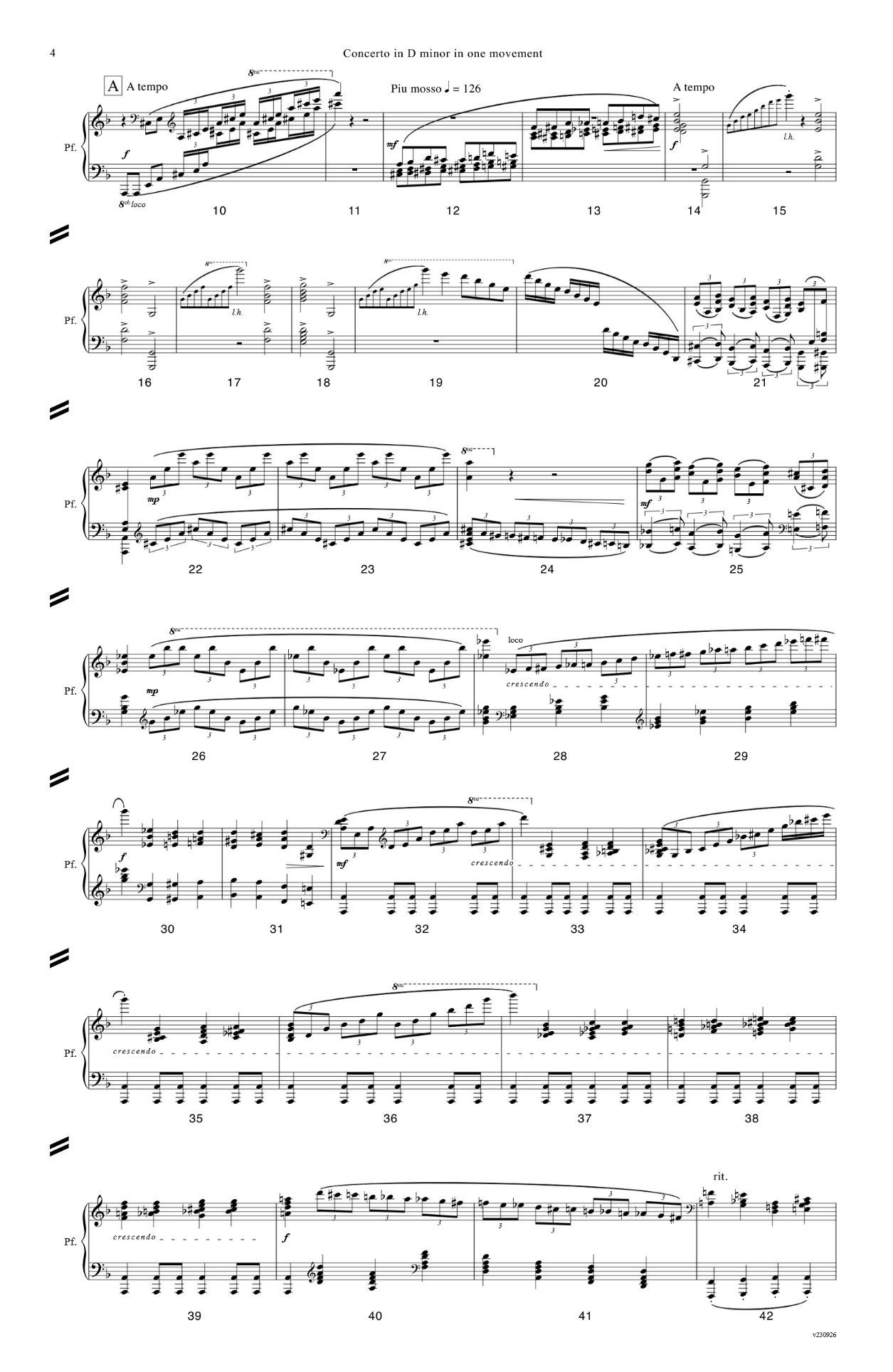

HC: As mentioned earlier, Price brought African American musical idioms into the classical forms—through symphonic structures, orchestration, and pianistic writing. The piano opens the concerto with an arpeggiated cadenza that unmistakably echoes Beethoven’s Emperor Concerto, while the string melody that follows, supported by broken chords in the piano, reminds me of Rachmaninoff’s Second Concerto. The call and response between oboe and piano draws on African musical traditions but also resembles the dialogic phrasing used occasionally by Romantic composers. The Juba dance in the final section—rooted in African American folk traditions—is masterfully realized for piano and orchestra. All of this demonstrates that Price’s concerto is a remarkably successful synthesis of African American and European influences, much like how Grieg, Rachmaninoff, and Dvořák integrated their own folk heritages into classical forms.

PJ: What kind of challenges or references did you run into while working on the tricky and emotional parts of the concerto?

HC: As with any new composer, understanding the stylistic nuances takes time. Since this was my first time playing Price’s music, I made sure to explore her other works—her symphonies, songs, and piano pieces. I found that her music has a directness reminiscent of Mozart. While it allows for Romantic expression, it should never be exaggerated or self-indulgent. Her voice comes through best when the music is played with simplicity and thoughtful precision. When I later worked on her Fantasie Nègre No. 1, I was able to make interpretative decisions more instinctively.

PJ: How does the one-movement structure work in terms of contrast and drama?

HC: Although titled Piano Concerto in One Movement, the piece is clearly structured in three sections: fast–slow–fast. The opening section, in an abridged sonata form, features alternating thematic showcase between piano and orchestra. After a brief pause, the slow middle section begins with a poignant call-and-response between oboe and piano. Another short orchestral interlude leads into the final section, which features the uplifting African American Juba dance.

PJ: What significance does Florence Price’s role as a Black woman composer and pianist bring to your understanding of this work?

HC: Her identity opens the door to understanding her inspirations. According to Rae Linda Brown’s biography, Price took pride in who she was, even expressing frustration when her mother was white-passing. She didn’t shy away from what she once described as the “handicaps of sex and race.” Price composed from a place of authenticity, choosing not to follow the avant-garde trends of her time. After learning about her life and musical language, her identity became a lens through which I could access the spirit of the music. Just as Chopin’s Polish heritage was important to him, it is ultimately his music that speaks to people—regardless of whether they fully grasp his cultural background; in the same way, Price’s music transcends her specific identity, allowing listeners and performers to connect with its emotional depth on a universal level. While I come from a very different background, I tried to let her spirit come through in my performance. After completing the project, I was struck by how long her music was forgotten—largely due to her identity. Given its brilliance, her work would not have been so long overlooked had she been someone else. This reinforces the importance of recognizing and overcoming bias, both artistically and personally.

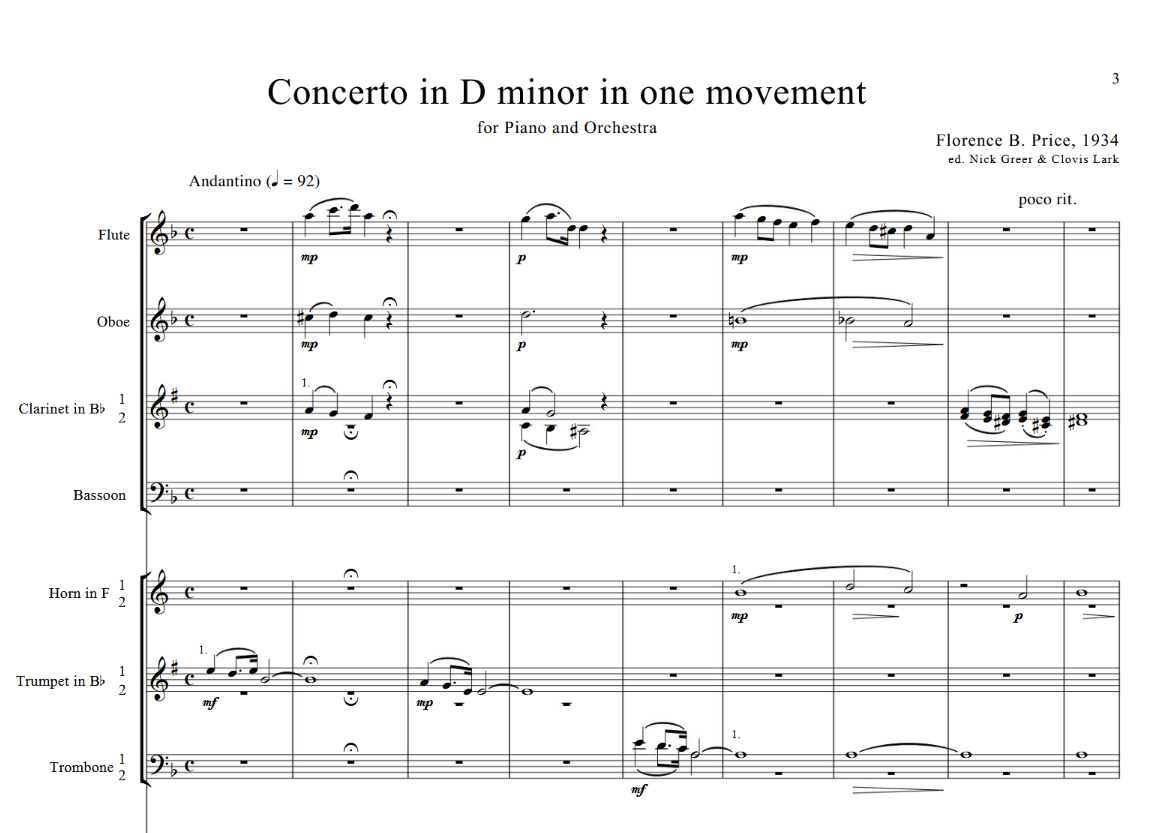

The introducing piano candenza of Florence Price’s Piano Concerto

PJ: What do you think makes this concerto a hidden gem of American music that’s been rediscovered?

HC: Price’s concerto fills a historical gap in the American piano concerto repertoire by blending African American musical idioms with the classical form. It is both thrilling to play and deeply rewarding to listen to. More importantly, this is a work of exceptional craftsmanship and profound artistic merit. Even without its historical significance, it would still deserve a place in concert halls on the strength of its musical value alone. Rhapsody in Blue is an American classic for piano and jazz band (not originally scored for an orchestra), but perhaps the next time we think about American piano concertos, Price’s Piano Concerto in One Movement should come to mind just as readily.

PJ: What do you hope people get out of your recording of this concerto?

HC: It has been an immense honor and joy to be part of this recording—from preparation, to sessions with the Malmö Opera Orchestra in Sweden, and now sharing it with listeners. I believe this is a strong and heartfelt interpretation of the work, and I hope those who hear it will experience the same pleasure and connection that I felt in bringing it to life.

Piano Concerto – full score:

https://issuu.com/scoresondemand/docs/piano_concerto_58911

Naxos Podcast: Florence Price – The concertos

https://www.naxos.com/News/Detail/?title=Podcast_Florence_Price_The_concertos

Stay in Tune with the Piano World

Join over 70,000 piano enthusiasts and get our exclusive monthly newsletter filled with classical piano news, inspiring articles, sheet music and other resources.

It’s FREE to join, and you can unsubscribe at any time.

Comments