Chopin and His Europe

The whole piano world is teaming up for the 18th International Chopin Competition to be held in Warsaw, 2 to 23 October 2020.

Initiator of the festival series ”Chopin and his Europe”, now on its 15th year, the recording project ”The Complete Works of Fryderyk Chopin on historical instruments” and ”The 1st International Chopin Competition on Period Instruments” (2018), Stanislaw Leszczynski of The Chopin Institute sat down with Piano Street’s Patrick Jovell at the Philharmonie in Warsaw.

The International Chopin Competition 2020

This grand occasion – taking place every five years – attracts the finest young pianists in the world and the competition is regarded as one of the most important venues for creating important international careers. Past laureates list an amazing number of world famous performers starting back in 1927 with Lev Oborin and include winners such as; Davidovich, Czerny-Stefańska, Harasiewicz, Pollini, Argerich, Ohlsson, Zimerman, Thai Son, Bunin, Yundi, Blechacz, Avdeeva and most recently, Cho. Other laureates include Ashkenazy, Ts’ong, Ushida, Fliter, Montero, Trifonov, Wunder and also non-laureates such as Pogorelich. Its influence on piano playing in the world cannot be overestimated.

Piano Street will cover the 2020 competition and as a starter we are happy to share an interview with an important profile in the competition’s history and programming which also includes a multitude of projects managed by The Chopin Institute in Warsaw, hi-lighting the influence of Chopin’s music in the world.

Interview With Chopin Institute’s Stanislaw Leszczynski

Patrick Jovell: Dear Mr. Leszczynski, we all know you as a portal figure in Polish music life. As deputy director of the Chopin Institute you are responsible for the prestigious International Chopin Competition. You have also initiated the “Chopin and His Europe International Music Festival”, and started a vast project concerning Chopin on period instruments, involving concerts and recordings of a number of world famous pianists. In September 2018 you arranged the 1st International Chopin Competition on Period Instruments. Tell me a little about your background?

Stanislaw Leszczynski: In 1978, I was appointed to oversee the classical recordings for the Polish record label Muza and I’ve been doing the same kind of job ever since. I became the first director of the Doslovski studio, which has very strong connections to both piano music itself and keyboard recordings. Our goal was to enrich the Polish Radio so that it could become like the Deutsche Rundfunk or the BBC. After much work, we have succeeded in creating many interesting and excellent recordings under the umbrella of the Polish Radio.

After that appointment, I also spent a few years as the director of the Polish National Opera, but I still kept in touch with the world of piano and pianists. When the Chopin Institute called a couple of years before the great 200th birthday jubilee, I took the job. I then had to examine the national composer of Poland from many different angles. It was extremely interesting to see the influences he had. He was smitten with Bach, who had died 60 years before Chopin’s birth. His background came almost exclusively from the great Leipzig master.

PJ: So, Chopin was a classical romantic?

SL: Well, not exactly. It must be stressed that Chopin was a Classical composer, not Romantic, regardless of when he lived. His compositions have very strict form and are quite precise. Because his music is intensely introspective – even when he’s being boisterous – he seems Romantic; however, his style is strictly Classical. Of course, he also looked forward. For example, Wagner wasn’t the only one to use the “Tristan Chord.” You can hear Chopin use the exact same harmonies on multiple occasions.

PJ: How is it possible to recreate a genuine Chopin sound?

SL: It would be impossible, of course, to perfectly recreate the sound Chopin made at the keyboard. We are, after all, not him. But through our research, practice and process of discovery, we can emulate the Polish master.

Chopin’s last Pleyel grand piano. Chopin Museum, Warsaw

What’s most difficult about approximating Chopin’s sound is that the new materials have different physical properties than the materials from the 19th century. The stuff reacts differently to being struck. For example, it doesn’t vibrate the same way. It’d be the same thing if a violin maker of today claimed to have copied a Stradivarius exactly. He couldn’t do it because not only is the climate for growing wood in the Mediterranean much different now than it was in 1680, the varnish isn’t the same because some of the ingredients no longer exist.

I’m really crazy about the history of both music and instruments. I would also like to travel to the future to see what kind of improvements they’ve made on our improvements. Haha, of course, I’m just joking. I do think, however, that it’s crucial to be able to compare sounds and construction practices between different eras.

PJ: Which are your thoughts on the subject “original instruments”?

SL: Well, not only were these instruments constructed using different techniques and materials, but they were also based on different tunings and centers of pitch. It doesn’t matter which composer the pianist plays, the two kinds of instruments, original and modern, sound quite different.

Let’s take, for example, Chopin’s Opus 10, No. 12, the “Revolutionary Etude.” Chopin wanted the two registers of the piano to sound different, which the 19th-century instruments did quite well. Contemporary models, however, are more homogenized, so we cannot achieve on them the same effect as we can on 19th-century pianos. These were not mistakes of construction; instead, they revealed a different philosophy.

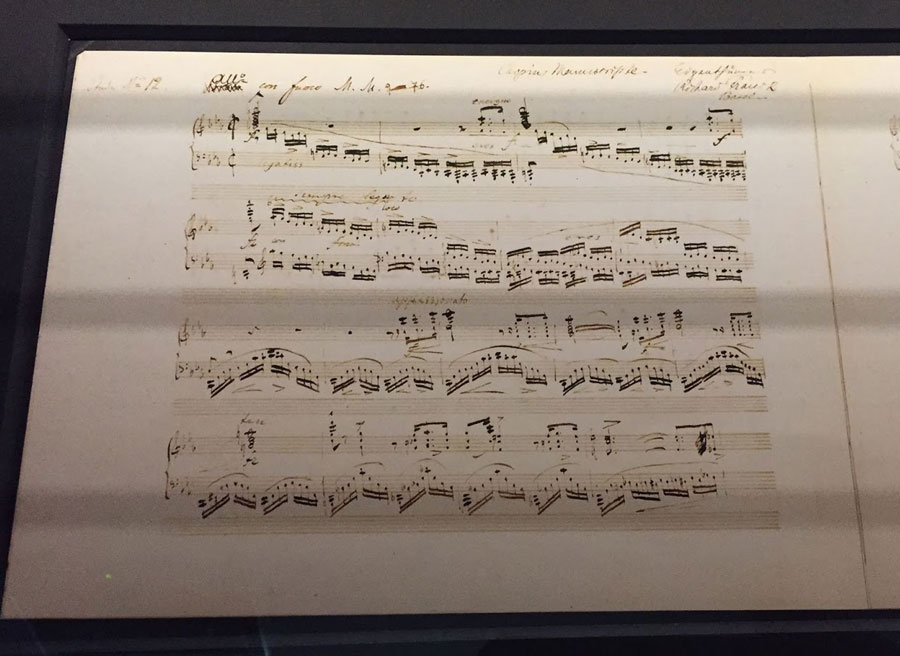

Chopin’s autograph of the “Revolutionary” Etude Op. 10/12, Chopin Museum, Warsaw

PJ: You have a great many years as part of this competition. What happened during this whole time span in terms of performance style?

SL: Nothing very special, really, although we do see, from time to time, different waves of performance style. Take, for instance, the large number of contestants in the 2015 competition who wanted to emulate the style of the 19th century. They don’t keep their hands together. They exaggerate certain phrases. Some of them are typically quirky. But they all have their own vision.

If you remember, critics in the 1970s were fond of saying, “the traditional Chopin interpretation is done,” and “Romantic music is passé”. There was a group of very strong American players from Juilliard that came to Warsaw for the competition. Ohlsson, Ax, Fialkowska and Swann, all showed up with their idiosyncratic styles that reinvented how we both play and hear Chopin. They blended 19th-century style with a more contemporary style and were quite successful at it. I can remember very clearly all their bravado. They all thought, “I’m the one! I’m going to win.” In the end, Ohlsson won, but you could have made an equally strong argument for Ax or the other incredible musicians who were flawlessly prepared.

In 1965, it was also incredible at the competition. Martha Argerich was out of this world in a class by herself. Five years before that, Maurizio Pollini was equally above the rest.

The year 1955 marked the first time that there were real and gigantic differences between the performers. Comparing Adam Harasiewich with André Tchaikovsky, for example, one would notice André playing a few too many wrong notes; however, the performance was electrifying in the same manner as Horowitz. One of the Japanese performers played completely differently than the other competitors, but it was, nonetheless, very interesting.

These young players were not alone, however. In the 1950s, there were still a great many members of the old school playing and being successful. The teachings of Philipp, Leschetitzky, Paderewski and others still made relevant contributions to the interpretation of not only Chopin but also other composers. Still, their differences from the more modern approach were not as pronounced as you might expect.

PJ: Considering your experience and everything you know of the history of Chopin playing so far, what do you think is the paramount quality in performing Chopin’s music?

SL: Well, I was on the preselection committee in 2015, and we were all listening to the 450 DVD submissions from around the world. The process took two weeks. We committee members asked each other the same question. My answer is still the same. It is the attention paid to the space between the notes that is crucial to the success of a performance, particularly of Chopin. The space between the notes is what underpins the structure of the musical line. Otherwise, the notes are just a jumble.

If we pay attention to the spaces between the notes, we could play “The Art of Fugue,” or “Die Kunst der Fuge,” on a collection of beer bottles and still recognize it. If such attention is paid, it matters not upon which instrument we perform a great work. It’s like musical rhetoric, with the spaces between the notes serving as musical punctuation. This is true in both the 17th and 19th centuries.

Expression is organized silence, but it is only half of the whole. A. B. Michelangeli, for example, was never a good Chopin interpreter; however, we loved him for the specific organization of both sound and silence that made him not a good Chopin interpreter.

The trick is to impress your will upon Chopin’s music without burying Chopin completely. If someone can do that, then that is something truly special. The best thing about this music is the diversity in expression. Piano students should never copy their professors’ sounds. I think they should all keep their individuality while still learning; in this way, we can discover someone and something new at any time. This lets us experience the joy of hearing Chopin for the “first time” again and again, which is something we all enjoy.

I International Chopin Competition on period instruments – Winners Concert

The Complete Works of Fryderyk Chopin on historical instruments:

http://en.chopin.nifc.pl/institute/publications/musics

The Eighteenth International Fryderyk Chopin Piano Competition 2020

COMPETITION SCHEDULE

13–24 April PRELIMINARY ROUND

2–23 October COMPETITION

2 October Inaugural concert

3–7 October First stage

9–12 October Second stage

14–16 October Third stage

17 October Celebrations marking the 171st anniversary of Fryderyk Chopin’s death

18–20 October Final

21 October First prize-winners’ concert

22 October Second prize-winners’ concert

23 October Third prize-winners’ concert

Comments

Great success, congratulations.

Have the Jurors been announced yet?