Natural Fingering – A Topographical Approach

“The black keys belong essentially to the three longest fingers” – CPE Bach

“Please do not think that I am so naïve as to ignore the logic of the circle around which our scales are built and the center of which is C. I merely stress that the theory of piano playing which deals with the hand and its physiology is distinct from the theory of music.” – Heinrich Neuhaus

The art of fingering is a huge subject, not least if studied historically. While many professional players stress the importance of good fingering we often find fingering suggestions offered by renowned editions to be clumsy, odd or simply out of place.

New York pianist and teacher Jon Verbalis book Natural Fingering is a rich resource on the subject of piano fingering. Verbalis delves into fingering techniques focusing on a topographical approach, and how they relate to the ideas found in F. Chopin´s un-finished Piano Method (Projet de Méthode).

New York pianist and teacher Jon Verbalis book Natural Fingering is a rich resource on the subject of piano fingering. Verbalis delves into fingering techniques focusing on a topographical approach, and how they relate to the ideas found in F. Chopin´s un-finished Piano Method (Projet de Méthode).

Thomas Fielden appears to be the first to have introduced the term “topography” in relation to fingering in his 1927 work “The Science of Pianoforte Technique”. Fielden stressed knowing how muscles and tendons work and how the arms and hands move. He scientifically analyzed which of these muscles and tendons a pianist used when playing and described the function of the finger, hand and arm as a lever used in the act of touch.

Verbalis also talks about equal temperament and how it affected composers’ choice of key signature. Further, he discusses the significant influence of Charles Eschmann-Dumur, who extolled the virtue of new fingering patterns. These patterns balanced groups of notes in major scales with equal numbers of fingers, which is a concept called equal construction. Equal construction allows the pianist to invert the finger pattern and keep the desired symmetry. This technique is especially apropos to contrary motion, where the two hands move in opposite directions. Verbalis quotes Dumur’s Exercises Techniques Pour Piano in order to buttress his conclusions. He also develops a fingering strategy based on the physiological construction of the human hand.

According to Verbalis the three working principles for a basic topographic fingering strategy are:

1) Long fingers on short keys (black), short fingers on long keys (white)

This represents the very essence of a topographical approach; from it the basic patterns and their pivotal functions evolve.

2) Fourth on black, thumb on white

The fourth finger is the ideal black-key pivot in diatonic scales and arpeggios.

3) No unnecessary stretches or adjustments

In regard to range of movement, it is most important to strive for fingerings with the aim of reducing or eliminating any unnecessary stretches or adjustments.

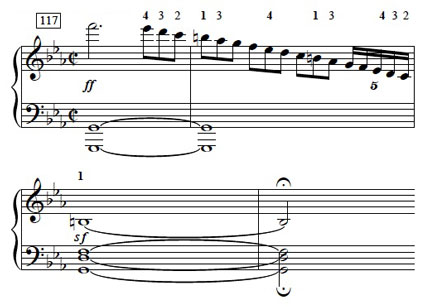

Example 1: Beethoven – Sonata op 13, 3rd mvt.

This descending scale does not suggest a traditional c minor fingering. The 4th on e flat allows the thumb instead of 4th on b and the 3rd on a flat becomes the pivot (principle 2) avoiding any positional stretch (principle 3).

Example 2: CPE Bach – Solfeggietto

Traditional fingering suggests the thumb on c (right hand). The 4:th finger on e flat supports the previous scale idea in c minor. 54323 from the g (right hand), is the c minor chordal position with a long finger (3rd) on black key.

Example 3: Chopin – Fantaisie Impromptu

The descending alternatives are to be tried from a hand size point-of-view. 453 from the d sharp gives us a diminished chord position down to the a, with a spread hand. The 342151 solution means two positions in the run. 4351 (g sharp, f sharp, a, e) supports the idea of long finger on black key.

Example 4: Debussy – Clair de Lune

The right hand descending basically follows the pattern of an E major scale (thirds). The 5th and 3rd on g sharp and e on the 6th beat in the second bar anticipates the chordal position of f sharp minor. The full f sharp minor 7 chord of the left hand is obtained through the 4th on f sharp, 3rd on a, 2nd on c sharp and 1st on e. Long finger on black key.

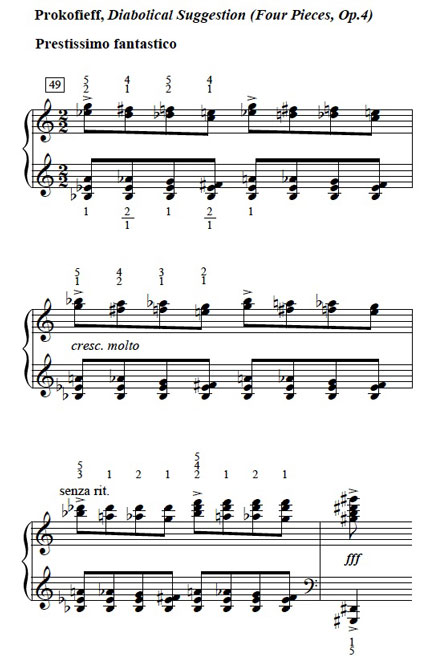

Example 5: Prokofiev – Diabolical Suggestion, Op. 4

The right hand is presenting major and minor thirds chromatically descending by using the 1st and 2nd fingers. The top voice descends through the 5th and 4th alternatively 5th, 4th, 3rd and 2nd (in bar two) in order to safeguard the legato line. The pattern is favouring a longer finger on black key.

Available on the Natural Fingering companion website (accessible through an access code) are excerpts from the repertoire which are provided with topographically correct fingerings illustrating the principles and strategies applicable to the content of each chapter.

Historical background

General concepts of fingerings can be traced to different schools of training and traditions but should ulitmately strive for the best solution in the given musical situation. We also must come down to the individual player´s situation where size and construction of hands will be crucial for the choice of fingering. We might ask us if there is an actual gain in knowing about Mozart’s scale fingering when his fortepiano displays no resemblance to a modern grand piano what so ever.

Chopin’s fingering principles

Chopin's fundamental hand positions for the right and left hand

In contrast to other pedagogues of his time, who sought to equalize the fingers by means of laborious and cramping exercises, Chopin cultivated the fingers’ individual characteristics, prizing their natural inequality as a source of variety in sound.

“For a long time we have been acting against nature by training our fingers to be all equally powerful. As each finger is differently formed, it’s better not to attempt to destroy the particular charm of each one’s touch but on the contrary to develop it. Each finger’s power is determined by its shape: the thumb having the most power, being the broadest, shortest and freest; the fifth [finger] as the other extremity of the hand; the third as the middle and the pivot; then the second [illegible]. And then the fourth, the weakest one, the Siamese twin of the third, bound to it by a common ligament, and which people insist on trying to separate from the third-which is impossible, and, fortunately, unnecessary. As many different sounds as there are fingers.” (F. Chopin)

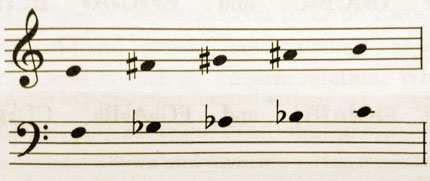

As an example of pure technique exercises that apply the concept of “keyboard’s proper relationship to the physiology of the hand,” Chopin would suggest that his students begin the study of scales with B, F# and Db Major (“following the basic fingertips 1-2-3-1, 2-3-4-1 and 2-3-1, respectively”). He considered that these scales follow the natural, comfortable position of the hand, due to the fact that the longer second, third, and fourth fingers would be playing on the black keys.

Neuhaus’ fingering principles

Legendary pedagogue and pianist Heinrich Neuhaus agrees with Chopin’s principle of each finger’s individuality but also refers clearly to the concept that the chosen fingering ultimately should serve the musical idea. Neuhaus says: “That fingering is best that allows the most accurate rendering of the music in question and which corresponds most closely to its meaning. That fingering will also be the most beautiful. By this I mean, that the principle of physical comfort, of the convenience of a particular hand is secondary and subordinate to the first, the main principle.”

Reader question

Which fingering principle do you use when playing the piano?

Please leave a comment below.

Examples reprinted from the companion website for Natural Fingering: A Topographical Approach to Pianism (April 2012), by Jon Verbalis with permission from Oxford University Press © 2012 Oxford University Press

Comments

Very interesting. Where I can to get the book from Verbalis?

I have always looked at the fingering offered in an edition, then made my own adjustments. For memorizing ,using the same finger pattern each time secures a solid technique and reinforces memory.

This focus on fingering is very helpful to me. I fear I regard fingering a new piece as at best a necessary evil and at worst a frustrating delay to getting started on the real work. Quite foolish,of course. Clear fingering makes learning so much easier.

The books are available on Amazon (hardcover and paperback)

The trouble for me with the writings of all those old-fashioned players is that their principles are all but useless for improvisation unless one wishes to restrict oneself to the type of sound made by classical music. Even outside improvisation, the sort of fingerings they used just do not work for the enormous body of jazz-derived idioms, stride, ragtime and other modern ways of playing.

In playing pieces, interpretation, we search for personally optimal fingering solutions to special problems; in improvisation we build general fingering solutions good enough to deal with all spontaneous ideas in a split second. Personally, I have found strengthening of the weaker fingers with a Virgil Practice Clavier invaluable in this regard, even if it runs contrary to all modern pedagogy.

Having said that, I still read anything that is going about these things, old or modern, in case I learn even one trick I can use in my own improvisation. Unfortunately, it just doesn’t happen very often, and I seem to play much better using movements of my own devising, particularly in the matter of rhythmic effect, which often seems linked to some really bizarre fingerings.

Please don’t forget that small hands are different from big hands. Be flexible, there’re no rigid rules !!!

One of the leading factors in choosing fingering for me arises because my middle finger is too big to easily fit between 2 black notes. So I try to save the middle finger (#3) for the black notes and ideally avoid using it for white notes, but especially avoid using it for white notes that are adjacent to 2 black notes (i.e., D, G, A). (This is because my middle finger is too wide to fit between 2 black notes without risking hitting 2 notes at once.)

I also want to comment on fingering for the chromatic scale. I use finger #3 for all the black notes, and fingers #1 or #2 for all the white notes. Such a fingering was commonly promoted in the 1800’s, but in recent times a “speed fingering” that also uses finger #4 has been promoted. I do not like the latter fingering and cannot play as fast or as evenly as with the former fingering. My test bed for this was the quite fast multi-octave chromatic scale on the last page of Beethoven’s sonata for piano and french horn. I can manage this with the former fingering but not with the latter. So I very much favor the traditional fingering that does not use finger #4.

For perspective, I’ve played piano for over 50 years and do a pretty good job on the Liszt Dante Sonata.

This is excellent discussion .. I agree with Bob Y about the chromatic scales but I’d like to hear more about fingering for repeating notes (one finger or multiple fingers) and also about how to efficiently move thumb “under” the hand in the scale. My old teacher always changed fingering based on my hand size – but one prevailing idea is to position the hand in such a manner that the finger is ready to strike a note (which is somewhat different from playing a scale!).

So, I´ve been a piano teacher already for 7 years, and I still love to practice new pieces and play for my self, my pupils or other audience. I tend to agree with Heinrich Neuhaus, as the musical idea of the composer is for me the strongest message in the manuscript. I try to find for every hand the best possible fingering, and I use the musical idea as a ´guide`for this. The result is a mix of the particular hand, and the fingering, in order to reveal the musical idea in its full depth and greatness

Top Publishers generally employ well versed and experienced score revisionists, that input academically recognized fingering Technics, suitable for the size of most instrument players,however,this fingerings are not necessary suitable for each individual,certain small hands or very large hands might require certain adjustments in certain areas of a piece.

It would be great for us all to be able to play an instrument with accomplishment without having to bother about what is correct or what is incorrect in fingering,in my opinion,a well trained-fingering has the advantage of making music playing fluid and effortless, without uncomfortable movements and interrupted execution, that makes music making a tiresome experience,in other words, trained fingering is the orthography of musical instrument execution.

“… other pedagogues of his [Chopin’s] time … sought to equalize the fingers by means of laborious and cramping exercises…

It’s easy to criticize the efforts of previous generations. And yet, neither Chopin nor any author since offered a better idea on how to achieve this necessary finger equalization in a way both effective and safe (i.e. without compromising the pianist’s health).

I believe it’s really necessary, even for expert sight-readers, to finger all rapid passage-work – both in order to play fluently and to memorise the score…However, I seem to find a minor problem with this: that you can’t be quite sure what the best fingering is until you know the speed at which, once you really understand the music, you feel the passage should be played. I often try to play the new passage at different speeds at the time when I’m first writing in possible fingering, to see if speed alters my choices…..but equally often I end up changing the fingering once I really get my head round the right speed – i.e. begin to get an overall vision of the piece. Any suggestions here, anyone, please?

Although I study the suggested fingering on scores I don’t generally adhere to them unless they feel comfortable. Instead I experiment with different fingerings to find which best suits my hands.

Chopin play’s the easiest of the major piano composers and his pieces tend to fit like a glove. It is clear that he really knew how notes and hands go together. Rachmaninoff on the other hand sounds great but his works are awkward for the hands and fingers and what the right fingering should be is anybody’s guess. (I wonder if there are any movies of Rach’s hands to see how he did it?)

Since the melody tends to be the highest notes in the score, the hand seems to be designed wrong. So many melodies carried on that little finger of the right hand. And the thumb, which could easily handle the load just plods along. And then in the bass, the little left finger is asked to do yeoman’s work. I wonder what piano music would be like if the fingers on the hands were reversed, as when you play cross handed?

Another consideration in fingering is the forearms and elbows. Some pieces are much easier to play if the motion of the arms and elbows are part of the process, for example the middle section of Chopin’s famous Op. 10 #3 E major Etude.

Hi, Jack,

Paola N here,

You are right about Rachmaninoff: his fingering would be useful only for himself due to his genetic defect: his hands never stopped growing!

And I agree with your question on playing with the hands reversed.

What baffles me is that the ‘modern’ pedagogy declared the necessary finger equalization (including the ability of the outer fingers to dominate) a wrong concept. And why? Only because it was unable to find the way to teach equalization both effectively and safely.

Many, too many, piano-players have already paid for this inability with their health and careers, and it doesn’t look like this situation’s going to change.

I am trying to imagine hands with the strongest and longest fingers on the outer ends of the hand. And should each finger then diminish in length and width working toward in the inner ends? Or maybe a surprise stronger finger right smack in the middle? :) Well, we will continue to work with our given hands and write our fingerings accordingly. Interesting article. Thanks.

To Lynda,

Hi,

Jokes aside :)

We need to recognize that the main features in piano music had not adhered to the nature’s design of our hands. In Romantic and post-Romantic music which stresses the outer parts (the contours), the outer fingers mostly need to dominate (while the inner need to be suitably subdued). In polyphony, all fingers need to be genuine partners, ready to apply either disposition at any moment…

Even the best fingering cannot help here.

I have seen master classes in Romantic music where hopefuls were adviced to “push harder” with outer fingers (despite already visible tension in their hands and arms).

Not a good idea, for neither their health nor the music they produce…