A score usually does not supply you with information about which hand played which note (there are exceptions when the composer actually does specify it).

In regards to piano music, all a score tells you is the keys that should be pressed and for how long. It is completely up to you with which hand you are going to press these notes and how you are going to

move between one note and the next. Intuiting this information (amongst other chunks of missing information) is ultimately what

interpretation is all about. If it was possible to give absolutely exact directions about every detail, the possibility of different interpretations would not exist anymore.

A score is a

model of the music, and as every model it contains deletions, distortions and generalisations, which are up to the performer to put back, undistort and specify. The most important (and seemingly obvious, but frequently forgotten) fact in all this is that – as Count Korzybski famously uttered – “The map is not the territory”.

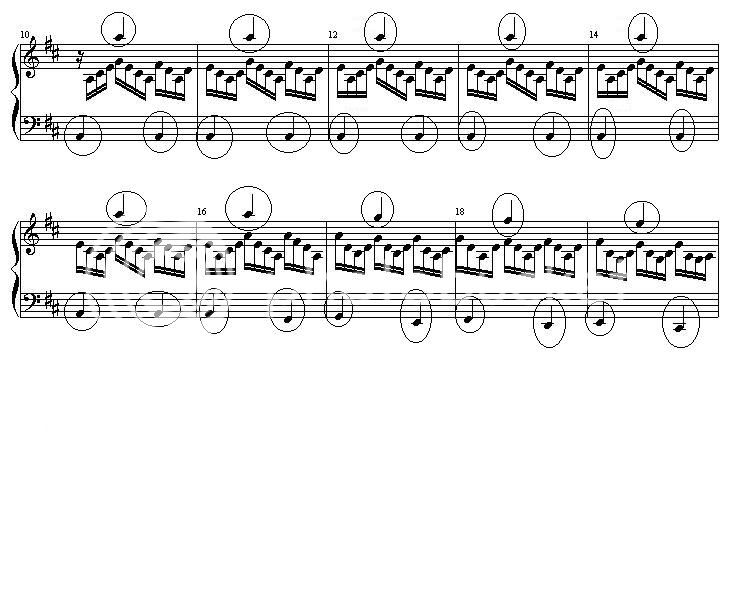

Having said that, it is far more comfortable and convenient to play the notes on the bass staff with the left hand and the notes on the treble staff with the right hand. If you do not you will have to play with hands crossed, which may be uncomfortable and inconvenient. Nevertheless, many pieces have been composed so that the performer must cross hands. The visual excitement generated by such a performance is many times enough to make one forget to listen to the music. Take the example below. It is the from Scarlatti’s sonata k27. The notes which I circled are to be played with the left hand, while the other notes are played with the right hand.

It is not impossible to play this passage without crossing the hands. However it is paradoxically far easier to cross the hands – that Scarlatti was very aware of the spectacular effect is evidenced by the fact that he went to the trouble to indicate which hand to use in the original score.

For certain pieces there is a body of tradition that tells one how to “interpret” (that is which movements to use and which sounds to aim at) even though there may be no explicit indication to that effect in the music. In other pieces such tradition is lost and it is up to the performer to decide how to play. In general, other things being equal, the main guiding principle should be comfort and ease of playing.

An interesting point is raised by Charles Rosen (an author and pianist I very much admire) in his book Piano notes:

It is important to realise that technical difficulty is often essentially expressive: the sense of difficulty increases the intensity. Composers will write in detail that sounds difficult but is actually easy to play in order to add sentiment..

Notice that Rosen is not saying that the performer should labour under incredible effort in order to intensify emotions, but that the passage

sounds difficult even though – from the point of view of the performer it may be quite easy to play (and I would argue that no piece is ready to perform until it has become

easy to play irrespective of how difficult it may sound or look on the page).

Crossing hands often falls into this category. To the public it looks amazingly difficult – but in general it would be amazingly difficult if not downright impossible to play the passage without crossing hands.

Have I digressed? I guess so.

So the answer is no: the location on staves, the way the stems go up or down, none of this really tells you about hand position or movement. Most of it is directed at telling you about the music’s

structure. For instance, stems up or down are usually indicative of the voice the note belongs to rather than which hand should play it. Of course, such information may be exactly what you need to decide which fingering/hand/movement to use.

Best wishes,

Bernhard.