I second this. I'm not sure how you can memorise before starting to play it. I can understand how it is possible but it sound very difficult. Do you have to visualise the notes playing at the piano before even sitting down to play it. If i could learn to that than essentially i could be doing piano work without even having a piano with me.

Are you familiar with Edna Mae-Burnan set of exercises for children “A dozen a day”?

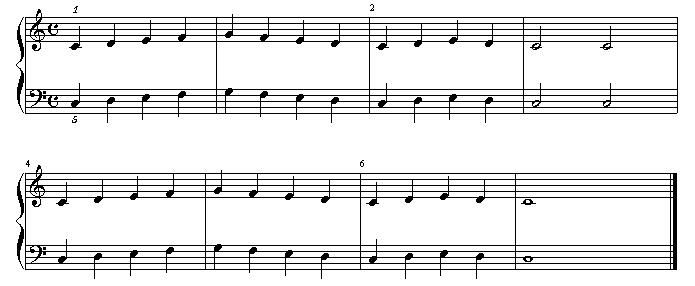

Here is the first one from book 1:

Get someone to record it on tape for you. Now sit at a desk, have some music paper and a pencil/pen handy, and a tape recorder with the tape of the exercise.

Look at the score. Notice the following:

1. Both hands are exactly the same throughout.

2. Hands are one octave apart.

3. The only notes used are CDEFG

4. The fingering is 12345 throughout – so the hands never move.

5. The first line is an exact repeat of the second line except for the last bar where instead of two minims (half note) you have a semibreve (whole note). This means that we only have to worry about the first line.

6. All the note values are identical (crochets/quarter notes) except for the last bars of the two lines where you have respectively 2 minims and a semibreve.

7. Notice the time signature 4/4 and the key signature (C).

8. Now concentrate on the first line. The first two bars are simply the five notes CDEFG in sequence going up and then down. In the next bar m they again go up and down, but this time they only reach the E before going down. So, make a mental note of that: C-G-C-E-C.

9. Now that you have noticed all that, put the score away, get some music paper and see if you can write it from memory. When you finish, check that it is correct by comparing it with the score, if it is not see where you have made mistakes, and go through steps 1 – 8 again, with special care on the bits you made mistakes. Write the score again, and check it again. Repeat until you can write the score without mistakes three times in succession.

10. Now go back to the original score. Read it and try to hear in your mind how the tune goes. If you cannot do that (it is a skill you learn – no one is born with it), turn on the tape recorder and listen to the tape as you follow the score. Now turn the tape off and try again to listen to what is in the score, in your mind. If you get lost use the tape again. Use the tape as much as necessary to be able to “hear” the tune as you look through the score (this is the same as reading a book and being able to “hear” the words being said aloud.). When you can hear the tune as you read the score, go to the next step.

11. Now get some music paper and write the exercise again from memory. But this time, let your

memory of the tune guide you. If you forget the next note, recall how the tune went. If you forgot how the tune went, look at the score you are writing and let what you are writing guide your inner hearing.

12. Now just look at the score. Imagine your hands at the piano in the proper position

see your first finger depressing the C, the second the D and so on. See yourself from the outside – as if you were in a cinema watching a movie of you playing the exercise. Put all your attention on this “seeing”: You want to remember what you looked like. Make sure you wee yourself with great posture and impeccable technique/movements.

13. Now see yourself again, but this time from the inside. You are inside your body watching your hands play the exercise. At this stage you may or may not need the score anymore. The score you use maybe in the table (real score), or it may be in your imaginary piano (there: you just got an instant photographic memory!). Since you are inside your body now, do not just watch your hands and the pattern of black/white keys you are playing, but also

feel the physical sensations of playing: the resistance of the keys, the muscles tensing and stretching, the motions.

14. Now do this again, but this time as you play your imaginary piano, “hear” the tune you are producing – which of course must be the tune written on the score.

15. Now, leave the score on the table, go to the piano and actually play it. If you followed all the steps above, I guarantee that you will be able to play this tune from memory and perfectly straightaway.

I have used a very simple exercise to make it easy to write about it. I would not dream of suggesting that you do this with Mae-Burnam’s exercises: they are not repertory. What I suggest you do is that you repeat the process above for fairly easy – yet superior – pieces of music. This way you will be training your memorisation and at the same time acquiring repertory.

This is exactly the same process you use to memorise a whole sonata. The only difference is that the sonata is more complex. The analysis bit (items 1- 8 ) will be lengthier. So you may start to see the importance of things like theory and aural training. Memory is based on association. Association requires meaning. Meaning is supplied by theory. You may of course develop your own private set of meanings – like watch the pattern of ascending and descending notes and compare it in your mind with mountains or rivers – which I suspect is what many jazz pianists who were musical illiterates were doing. But you must come up with a set of meanings, otherwise, all you have is meaningless dots on a page, and this is truly impossible to memorise.

I suggest you have a look at Walter Gieseking & Karl Leimer “Piano Technique” (Dover) which describes in much more detail a very similar process and provides several examples from the literature (Gieseking was famous for only going to the piano with the pieces completely memorised form the score).

The obstacles you will find have little to do with memory capacity. The approach above must be done systematically and consistently for a number of year before you become truly competent. This means 10 minutes a day everyday memorising a piece or passage. The size and difficulty of the passage will depend on your stage of musical development. The best approach is to stick to ten minutes. Anyone, even a beginner will be able to memorise Mae-Burnam’s exercise above in ten minutes following these steps. Soon you will find yourself being able to memorise similar passages in a couple of minutes. That is when you upgrade the stakes: choose a more difficult passage, or a longer section and see how you fare. Anything you repeat everyday following the steps without skipping any and without cutting corners soon becomes automatic, and soon you find yourself memorising even without meaning to.

But everyone is impatient and inconsistent. Everyone cuts corners, skips steps and after two days of regular practice they forget about it all.

Finally, as Cooke said, do not know a piece because you remember it, but remember a piece because you know it.

Does this help?

Best wishes,

Bernhard.