Moonlight Trapped in the Sonata Form?

Sonatas come in many shapes throughout the history of music. The name Sonata is derived from the Italian word “suonare” (to sound) as opposed to “Cantata” (to sing). Although we find many single movement pieces from the Baroque period and mid-18th century named sonatas, it is not until Haydn, Mozart and Beethoven develop a 3 (or 4) movement disposition that we can talk about the term ”sonata form”. They all added extra movements in order to create what Leonard Bernstein later explained: “… perfect three-part balance, and second, the excitement of its contrasting elements. Balance and contrast — in these two words we have the main secrets of the sonata form.”

The popular classical form

For both Haydn, Mozart and early Beethoven it is still the first movement in the sonata which stands paramount in the construction. Additionally a slow movement and a fast movement could be added, each having a specific function in the musical argument of the complete piece. Beethoven eventually develops the form and strengthens each movement’s own specific character and even re-disposes the number of movements and alters the fast-slow-fast disposition of the Classial era.

How can we explain this immense popularity of the sonata for over two hundred years? What makes it so satisfying, so complete?

In Beethoven’s hands the piano sonata underwent a drastic development from his early works inspired by Haydn and Mozart until his late experimental and bold works with a much freer concept of form and drama. The term “sonata form” appears in the mid-19th century and Beethoven’s 32 piano sonatas were the basis for the analysis.

The Moonlight Sonata is different

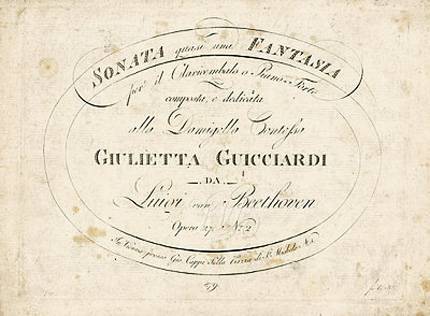

There are no specific reasons why Beethoven decided to title both the Op. 27 works as Sonata quasi una fantasia (“sonata in the manner of a fantasy”), but the layout of no. 2 (the Moonlight Sonata) does not follow the traditional fast–slow–fast. Instead, the sonata proposes an end-weighted journey, with the rapid music held off until the third movement. The sonata consists of three movements:

There are no specific reasons why Beethoven decided to title both the Op. 27 works as Sonata quasi una fantasia (“sonata in the manner of a fantasy”), but the layout of no. 2 (the Moonlight Sonata) does not follow the traditional fast–slow–fast. Instead, the sonata proposes an end-weighted journey, with the rapid music held off until the third movement. The sonata consists of three movements:

Adagio sostenuto-Allegretto-Presto agitato

The name “Moonlight Sonata” comes from the German music critic and poet Ludwig Rellstab, five years after Beethoven’s death.

Beethoven: Sonata Sonata Op. 27 no. 2, piano sheet music:

Two distinctly different interpretations

Here we listen to a recent performance of the Moonlight Sonata by pianist Yundi Li from a popular TV-show in Japan. His interpetation is quite traditional with a slow and beautiful rendition of the first movement while his last movement is very clean and polished – indeed not one of the more wild and stormy versions we have heard. But that is perhaps what to expect by Yundi Li, who is a former International Chopin Competition winner (2000).

On the other hand we have Andras Schiff who, in recent years, has proposed a completely different interpretation of the first movement for three resons:

1. The nickname “Monlight Sonata” is nonsense.

2. Since the meter is “Alla breve” we should count two beats (half notes) per bar, calling for a quite light and quick tempo.

3. Beethoven writes in the beginning of the piece “Si deve suonare tutto questo pezzo delicatissimamente e senza sordino” which means “This whole movement must be played with the utmost delicacy and without dampers. (i.e. with right pedal down). If that means that we should keep the right pedal constantly down throughout the piece or to change pedal in a traditional way when harmony changes is the big question for debate.

Listen to Schiff’s lecture below for a more detailed description.

Yundi Li plays Beethoven Sonata Op. 27 no. 2 (from Japanese TV 2014)

1. Adagio sostenuto

1. Adagio sostenuto

2. Allegretto

2. Allegretto

3. Presto agitato

3. Presto agitato

Andras Schiff:

Lecture about the Moonlight Sonata (Wigmore hall, London)

Lecture about the Moonlight Sonata (Wigmore hall, London)

Reader Poll

After voting:

1. Feel free to post a comment below about your choice.

2. Share this page with any of your friends that would be interested in reading it and voting.

Comments

It’s a slightly unfair comparison, as Schiff’s performance has the benefit of an erudite and insightful lecture to back it up. I’d wager that if Yundi’s performance were also accompanied by an explanation, especially a charming and witty one such as Schiff’s, he’d be far ahead in this poll. (Given that it’s not, it’s a miracle the vote is as close as it is.) Such a lecture might highlight the benefits of the slow, mesmerising tempo (which may or may not have been what Beethoven intended – my guess is that if he heard it played like that, on a modern piano, he’d have absolutely loved it). To my ear, the fast tempo makes it sound like a waltz (less so when Schiff does it, as his interpretation is so fine and so steeped in reverence for the music, but certainly when others play it at that speed). Playing it that fast can almost reduce it to farce, and can certainly make it sound like the pianist is in a hurry to get it over with. Yundi, on the other hand, is totally immersed in the sound world he has created, and that was also my response as a listener. To me that immersion is what music at its best is all about.

I voted for Yundi Li for as soon as I heard it I thought of Beethoven saying that to “play without passion is unforgivable” and his version moved me

with the deep emotion he showed in playing.

What exactly is meant by senza sordini? Did Beethoven actually mean that third pedal to the left which many pianos don’t have nowadays. Press this down and you will get a much softer and quieter sound as the strings are semi damped. Was Beethoven asking pianists not to use this pedal to get a true ppp effect?

I personally prefer neither version. IMO Solomon got it right where his stronger emphasis on the left hand created an entirely different effect.

Both performances are awful in their different ways. I could not vote for either. Yundi Li is ponderous and makes a horrible hesitation on the third beat of each bar. He seems incapable of playing steady triplets against dotted quaver/semiquaver in strict time. Schiff sounds hurried and the excess pedal just creates an ugly sound. Both of them overemphasise the first note of each group of triplets. These are world class pianists but they clearly have no understanding of this piece. They should stick to playing music that they do understand.

Schiff’s scholarly analysis is enlightening and significant; however, my spirit resonates more with the sound of the traditional interpretation.

I voted for Schiff and would use his approach on both fortepiano and modern piano. Some thoughts:

1. How do we know that senza sordini means “without dampers” and not “without damper pedal”? Because for many pianos of the period there was no “pedal” – the dampers for these instruments were operated with knee levers; other pianos did have pedals. Composers therefore tended not to refer to the mechanism but to the effect operated by the mechanism, i.e. with or without mutes (sordini), that is with or without dampers. Primary sources from the period make this quite clear.

2. It’s not that helpful to refer to historic Viennese pianos and the English Broadwoods in the same breath. The Viennese instruments with their leather-covered hammers tended to be more articulate and less sustaining in sound. But the Broadwoods tended to create a more boomy, blooming sound and could be *very* resonant. Composers like Haydn wrote very differently when they anticipated performance in England. Beethoven was known to prefer Broadwood pianos, presumably for these qualities. Both types of instruments were capable of damping the strings with equal efficiency. So what’s more relevant is the quality of the sound undamped, and the Broadwood would certainly have offered a more blurred sound when played with the dampers raised.

2. “Great delicacy” plus “without dampers”. That’s the crucial combination. I would add that a senza sordini performance requires great flexibility. One of the effects of leaving the dampers up is that the musician then needs to really listen and make subtle adjustments to touch and pacing (rubato if you like) as the harmonies change, depending on the nature of the harmonic change. In other words the style of performance is precisely like that of a fantasia as described by someone like CPE Bach at the end of the 18th century.

3. This raised dampers effect was by no means an unknown before this sonata. Haydn uses it in his late C major sonata (Hob.XVI:50, admittedly not for a whole movement, just a line) and there are descriptions of the technique, which was much admired in fantasia-like pieces such as this Beethoven sonata.

3. Nanette Streicher, one of Vienna’s leading piano builders of the day, loved this exotic effect (1801): “Now in pianissimo, through [the raising of the dampers] he creates the most tender tone of the glass harmonica. How pure, how like a flute, the treble notes sound while the left hand plays consonant chords against them! How full the sound of the bass which is played with elastic lightness!” She also adds: “the true musician introduces such beauty sparingly, so that too frequent use does not spoil its effect.” Clearly Beethoven is pushing the envelope here by recommending it for a whole movement, but this should hardly be a surprise – he was always pushing the envelope.

To me the final result of a senza sordini performance is unusual, striking and very, very beautiful. As Schiff says, the initial reaction if you’ve never heard or tried it that way before is shock. “Not how your grandmother played it!” But this is definitely a scenario where going back to the composer’s instructions and being bold enough to try to follow them yields a wonderfully satisfying (and revealing) result.

I much prefer Schiff’s interpretation. His lecture is very interesting but more importantly I found his interpretation more engaging than Li’s which was too polished for my tastes.

Schiff is not the only pianist to play the Adagio in Cut Time and at a less slow tempo. Murray Perahia plays it in a similar way. Perahia also noted that most people play the first movement “too slow”.

Hello everybody:

I think the election is clear. First of all Schiff is far much better piano player than the Li´s . Secondly, his interpretation is much more interesting and coherent. The explanation helps, but It is a matter of great superiority as a pianist and musician. You can have your own ideas about the sonata but you have to be a great musician to convince the listeners. And I like the way he plays the first movement, it has a lot of mistery.

Greetings

I have always played it not quite as fast as Schiff, but much closer to the speed he takes. I do also shape phrases with very slight rubato to bring out the drama of the beautiful melodic phrases– and I believe Beethoven did this as well. They were already playing with slight rubato in certain pieces –perhaps we should actually call it “rubatino” :-) before the term “rubato” was used and done in a more pronounced way in Chopin’s era 20 years later.

I think Beethoven would played it like Andras plays it.

Well both are quite nice, but I still prefer the more traditional sound. I prefer the slower tempo. Many people say that people play this piece too slow, but what does too slow mean. Music is all about what you want to put in it. Slow is you preference or ability then go for it. I would not be too worried what others say about your music. It is important to take constructive criticism though. I did like the dynamic contrast in both interpretations.

I think Adrias is correct (and humorous, too!) . I used to play in both tempos and I like Beethoven’s Opus 27 played the way he wants(wrote) it played. Adrias’ interpretation is next to thinking the way Beethoven thinks. With the pedal down, I think that it would give more emphasis on the harmony while sustaining the melody. Playing it too slow (and using the damper) will only “sprinkle dust” to a very beautiful piece of music.

I usually don’t vote when there are complex issues asked, since other choices should be given but hardly ever are: namely, “both” or “neither”.

In this case I would have voted “both” for the richness of genius is that there can often be numerous ways to interpret a masterwork (as many lf the comments imply) and I find it fascinating and educational to be able to consider serious attempts at guessing original intents.

I am not a professional pianist but I love it and play piano very often.

Yundi played very nice way, but I am much impressed when the piece to be played by Schiff’sinterpretation, it is similar my own interpretation and be the way I love.

I really didn’t want to vote for either because they are of course both very valid interpretations. However, I voted for the Schiff one because I felt Yundi Li’s was just a little too slow and his affect was just a little too much for me. I do believe the “alla breve” marking is bourne out in Schiff’s interpretation very well; however, I will have to reserve judgment on the continuous pedal until I can hear a clearer recording or try it myself, which will be very interesting.

I enjoy the quicker tempo Schiff uses. We know this piece so well that the Yundi tempo seems draggy .The chord structure is slow enough to be understood faster. My attention wanders when played too slowly.

This may be a fault of modern audiences impatient with sitting through the obligatory hour and half recitals.

1. MS played slow so kids can play it. It looks very easy. I remember doing this at age 8 or 9.

2. What would the sonorities be like on a Beethoven-era piano?

I have some Chopin done on a Pleyel and it sounds very different. The different registers are distinct on 19th C instruments.

Yundi plays well as always, but his it is not an unforgettable interpretation (like Paderewski, Schnabel, Nat, Backhaus are)

Andras is more original, even if questionable as pianos of Beethoven age had less persistence of the souds, and Beethoven was already a bit deaf, nonetheless such pedalling is requested in other pieces by Beethoven, like in 3rd mov. of Waldstein, and rarely we hear them (Schnabel did), even if results in the hands of a great pianist are often astonishing

No offence to Mr. Li, who obviously knows his way around a keyboard.

But–why not speed it up a bit? Mr. Schiff’s interpretation is an interesting alternative.

Thanks for the interesting article. I liked both performances but voted by Andras and his in-depth research of the work in question.

I like the slower version of playing this song, but that’s because that’s my style. I tend to slow things down a little and add emotion to what I’m playing. I also think it keeps a little mystery, as the original name suggests. Schiff has a good point when he breaks down the comments that Beethoven made. I think it can be played in the same style as Hindi, but possibly a little faster

It doesn’t seem fairly to me to vote for one of them, to “point” at one and push aside the other, maybe this is beautiful in art, that different visions can stand at the same time :) New interpretations are always welcome when they are made in the service of the truth… The first performer’s condition has to be sincerity, so if he is traditional or “weird” it’s a question of structure, culture, taste… The votes will not indicate that one is better than other, it will only show which kind of people is preponderant here and now… As a humble teacher I can say that I really enjoy Mr. Schiff’s lectures, he reveals the personality of Beethoven so well, adequately explained, also using a charming humor, all he says becomes disarmingly in a way… Regarding the controversial topic “senza sordini”, I don’t see perforce one single pedal during the whole movement, I see instead, the whole movement permanently pedalized, which doesn’t contradict the indication “without dampers”. So, in my vision, it is left to performer’s skill and fantasy to “speculate” and “juggle” with the harmonies…

I am always amazed that this sonata in invariably included in “Easy Listening” collections, usually played at a glacial tempo. To me, it is so loaded with tension and emotional depth that it scared me when I was a child. It is one of the many joys of the piano that I can play this great work exactly the way I want, which is closer to Mr. Schiff’s interpretation.

Many thanks for this discussion.

in my opinion is very important the bass and the armony as well as in the jazz music.

Certainly Shiff’s version! It sounds so much better and it is genuine. Thank you for the great article!

It lacks a third party, the excelent one: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=O6txOvK-mAk

Pianos in Beethoven’s time were (of course!) much different from ours, so we have to listen to a rendering on such a piano,if there still is one with the ORIGINAl STRINGS (read Rosamond Harding’s:The Piano-Forte).Also look at Beethoven’s music to understand what he in fact means with Adagio tempo.Is it different in some opusnrs.?.For instance the second part of the Sonata Pathetique,is almost always played much to fast.

I didn’t really like either version alone. I believe it should be faster, as keeping in line with Beethoven’s intentions, but agree with many of the other comments about the pianos in use at that time. Modern day pianos playing even pedaling at every chord change create a much muddier sound than using that same technique on the pianos of Beethoven’s time. I agree with the comment that there should be pedaling, but with a light touch.

I believe the faster tempo is in closer agreement with the third movement of the sonata, a fantasy in concept. Today’s pianos can’t bear a continual pedal without giving a muddy sound. Also, Beethoven’s tempo indications were sometimes given to offset the tendency of pianists of his time to play too fast. We even see the same tendency rearing itself today.

With regard to this piece,I like the original translation of Adagio as”at ease” which if played as Andras Schiff does, gives the music a sense of movement forward.

I voted “tradiional”. Mr. Schiff’s interpretation was excellent but the predominance of undamped notes made it sound a bit “muddy” to me. I subscibe to the notion that the modern piano’s long sustain not working well with Beethoven’s original instructions.

I have always felt the slow tempo felt “held back” as if meant to move along a bit more. I voted for Schiff’s version because I tend to want to play it faster than the traditional. I really feel, however, that somewhere in-between these two tempos would be a better choice. Even a funeral march isn’t speedy! Both are beautiful and I enjoy the different interpretations and discussion about why. Great article. Thanks

It’s has been very interesting to compare the two version ! So I have to say that none of the two really convinced me 100 %: Yund li sounds “pop” music or Hollywood and it that sense sounds more “modern”; the other two movements played by Yumd Li showed that he does not understand what he’s playing and this is particularly true when you lissen to Andras playing these movements in the lesson.

I dont’ really think you can compare this two artist; Andras is coming from the old classical tradition and Yund Li is just playin the notes excactly and keeping always the same time. Regarding the first movement played by Shiff (I voted this one) I think there are one or two moments where it’s a bit too much dissonant. To finish my favourite is Kempff version !

In any discussion of musical interpretation and recreation of any composition we should ever be aware of the nature of Music—that it is necessarily and gloriously subjective, will never permit pigeonholing, and will aways amaze and intrigue with its infinite and often surprising ability to become something we never dreamed of. We have loads of evidence that the Great Composers themselves deviated from their scores or embellished them in startling ways depending upon mood, impulse, inspiration, and intention. As has been well said, “The music is behind the notes.” There is no “correct” Moonlight Sonata. It can be played with genius whether fast or slow, whether in 4/4 time or 2/4 time, with or without pedal, with or without accents and tempi changes. In fact there are an infinite number of Moonlight Sonatas and none of them can ever be played the same way twice. The music is greater than the instruments that render it, greater than the minds that interpret it, perhaps greater even than the minds that offered it. Personally, I find Andre Schiff’s comments certainly authoritative, interesting, and provocative, but not the Word of God. Even if his source theory is correct (from Mozart, not moonlight) I find his interpretation somewhat too perfunctory for a funereal piece, not enough agogic, not enough rubato, not enough agony, and too fast and driving for the devastation of death. I would have liked to have heard Scriabin play it.

Although Yundi Li gives a beautiful performance of the traditional version, I agree with Andras Schiff’s faster tempo. I believe the faster tempo prevents the melody line from becoming “separated.” (There actually is a melody in there). I don’t agree with the continuous pedal, however. My understanding is that the pianos of Beethoven’s day couldn’t sustain a note for an extended length of time, so he wrote the instruction “senza sordino” to compensate. However, the modern piano doesn’t need that “help.”

Is it really dichotomous? I see it as more dimensional and to my taste both of these interpretations are to close to the poles. But what a joy to here the argument put with such authority. Thank you.

Somehow i feel Yundi’s version is much better. The way he performanced shows the aesthetics from Asia people.