Volodos in Vienna

“You can keep your Lang Langs, your Yuja Wangs, your Evgeny Kissins… I’d swap their collective virtuosity for one evening of Arcadi Volodos’s consummate pianism. To my mind, he has produced nothing finer on disc than this live recital, captured in Vienna last spring.” — Gramophone Magazine Volodos in Vienna is a recital album by Arcadi Volodos recorded live at […]

Sigismond Thalberg’s 200th Anniversary

The recent anniversaries of Chopin and Schumann in 2010 and Franz Liszt in 2011 inspire us to once again travel back in time and set focus on another tremendously important, yet almost forgotten virtuoso pianist from this golden era of pianism: Sigismond Thalberg. Sigismond Thalberg was born in midwinter in 1812. Wednesday, 8 January 1812 saw not only the birth […]

The Battle Between “Il penseroso” and “The Old Arpeggio”

Before the time of television and the internet, live music performances were a primary form of entertainment. Performances were held in private homes, as well as concert halls. Many rivalries formed among pianists and composers. This created a unique angle for entertainment as individuals could then debate the merits of each musician and choose sides. One of the more famous […]

The Complete Liszt Coverage – Dr. Alan Walker’s Liszt Biographical Works

Alan Walker’s three-volume biography of Franz Liszt, which took him 25 years to complete, has been very influential. Common adjectives attached to the work include “monumental” and “magisterial” and it is said to have “unearthed much new material and provided a strong stimulus for further research”. Walker himself says that when he found, as a BBC producer compiling notes for […]

Prize Winners in Utrecht Celebrate Franz Liszt

To celebrate Franz Liszt’s 200th birthday, the Liszt Competition Utrecht organized a unique concert at the Vredenburg Concert Hall. The organization made a huge effort to bring out the best of 25 years of Liszt Competition history: all nine 1st prize winners were gathered here to play some of their beloved composer’s less familiar works. Some pianists shared the stage […]

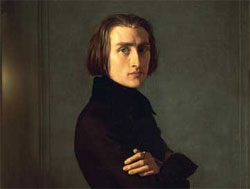

Franz Liszt – 200th Anniversary

Today, October 22 2011, marks the 200th birthday of Franz Liszt, the greatest piano virtuoso of his time, inventor of the modern piano recital and one of the most influential composers of the 19th century. Piano Street here presents a collection of material and links to resources for you to enjoy in order to commemorate the great Franz Liszt. Happy […]

The Hungarian Liszt..? Exclusive interview with pianist Klára Würtz

In order to attract extra attention to the international Liszt year 2011 celebrations, Piano Street’s Patrick Jovell assisted by Alexander Buskermolen had the unique opportunity of speaking with internationally renowned pianist Klára Würtz. An international competition prizewinner with numerous notable recordings for the Brilliant label, Ms. Würtz was born and trained in Hungary and graduated from the Ferenc Liszt Academy […]

Recommended book: The Piano Master Classes of Franz Liszt

The piano master classes of Franz Liszt 1884-1886, Diary notes of August Göllerich by August Göllerich Indiana University Press, 1996, ISBN: 0253332230 Göllerich was student, secretary and companion to Liszt during the musician’s last two years (1884-86). The diary contains the dates of the master classes, lists of performers and the works they performed, and some general thoughts and reflections […]

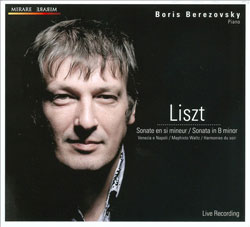

Grand Style Liszt with Bererzovsky

NEW! Click the album cover to listen to the complete album: (This is a new feature available for Gold members of pianostreet.com) This CD, a collection of live recordings taken from performances at the Royal Festival Hall and the Festival de la Grange de Meslay, provides yet another example of Boris Berezovsky’s stunning virtuosity and musicality. A Liszt recital, the […]

Kissin Giving Liszt to the World

Evgeny Kissin is a great pianist in the Russian tradition, with the sweeping style, generous tone and powerful but supple technique that marks an heir of Rachmaninov. But for him, music is a language and performance is about communicating meaning, and he can conjure a world of imagination – reflective and insightful – even as he dazzles with his astonishing […]

New Sheet Music: Liszt – Transcriptions of Songs by Schubert

Transcriptions and paraphrases played an important part in shaping Liszt’s role as leading musical figure of his generation. The first pianist to play the entire range of the keyboard repertory from Bach to Chopin, his historical curiosity and ambitions did not stop there. He transcribed both famous and less well known vocal and orchestral works of others in order to […]

Khatia Buniatishvili in Search of Faust

Acclaimed young pianist Khatia Buniatishvili’s debut album for Sony Classical is devoted to Franz Liszt. Although she sees herself as belonging truly to the 21st century, like the Romantics, she looks for greatness in small things, for the universal in the individual. And in the music of Liszt, she seeks and finds her idea of musical completeness and pianistic perfection. […]