[continued from the previous post]

The second, naming the chords, I can't do without help. The first set of cords are (as xvimbi already noted), the 1st inversion of I (I b), but I am alreay stuck in the 2nd. It seem to be II, but what do I do with the top E? and then it seems the E gets diminished , but I do not know how to name it, since I can't name the 2nd set. Help!!! It feels like doing math again....

Ok. Let us go bar by bar. Asyncopated could not quite understand my tables

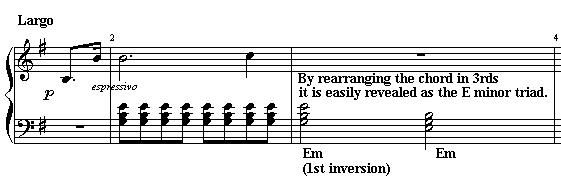

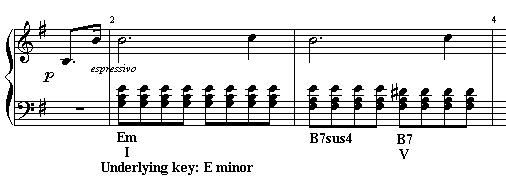

, so as I go along I will explain how to use them. Here is the harmonic analysis for the first three bars.

Here are the first two bars (even though the first bar is an anacrusis and it is usual not to count it, I usually do count it):

As you already found out, this is straightforward enough. On the left hand we have the triad of E minor (inverted). Now if you look at the table of triad genesis, you will see that the E minor triad can be generated from the following scales:

D major – the E minor triad would be generated from degree II.

C major – the E minor triad would be generated from degree III.

G major - the E minor triad would be generated from degree VI.

E minor (harmonic) - the E minor triad would be generated from degree I.

B minor (harmonic) - the E minor triad would be generated from degree IV.

E minor (melodic) - the E minor triad would be generated from degree I.

D minor (melodic) - the E minor triad would be generated from degree II.

Having established earlier on that this prelude is in E minor, it is quite safe to assume that this triad is indeed the tonic triad, originating from the E minor scale. So, the prelude produces both its melody and its accompaniment in the first two bars from the underlying key of E minor.

So far so good. We have identified the chords, and we have identified the underlying key (at least provisionally – all this depends ultimately on context – as we go on, we may find that our initial assessment of underlying key may have been wrong).

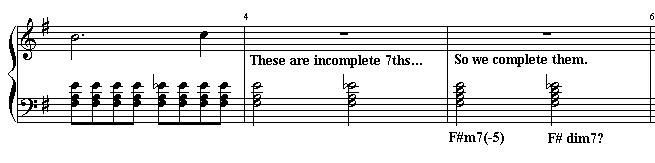

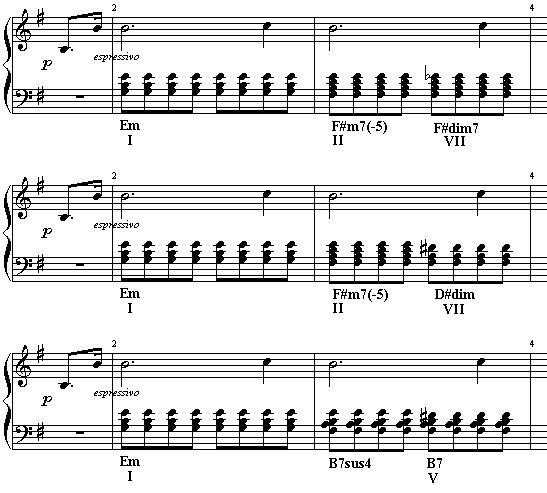

Now all hell breaks loose as we face the third bar. There are two chords there. But what are they?

If we consider chords to be stacked thirds, clearly these are incomplete 7th chords. So let us complete them:

Now, considering the thirds that form those chords from bottom to top, we have for the first chord: minor – minor – major. If we look up the table of Seventh genesis, we have a minor 7th dim 5 chord, and since the root is F#, this is a F#m7(-5) chord. Again, referring to the table, we can see that such a chord can be generated from the VII degree of the G major scale, or from the II degree of the E minor (harmonic scale). It could also be generated from the VI degree of the A minor (melodic) scales, or from the VII degree of the G minor (melodic) scale.

Chances are, of course that it was generated from the II degree of the E minor (harmonic) scale. So we can breathe again. We are still in E minor as the underlying key, and the chord, although unusual is perfectly within the diatonic rules of chord formation.

What about the second chord?

Here Chopin introduces an Eb, a note that is completely unrelated to the E minor key. And if we complete the thirds, the result is a 7th chord formed by the following thirds (bottom to top): minor – minor – minor. Going back to the table, we have a diminished 7th chord, the F#dim7. This chord can only be generated by the VII degree of the G minor (harmonic) scale. So, what is going on here? Has Chopin suddenly modulated from E minor (with F# in the key signature) to the relatively distant key of G minor (Bb and Eb on the key signature)?

Is this Eb just a chromatic note added to create dissonance? After all, half a bar ago, in the melodic line he placed a B natural. If this Eb indicated a modulation to G minor, we would have expected the Bs to go flat as well.

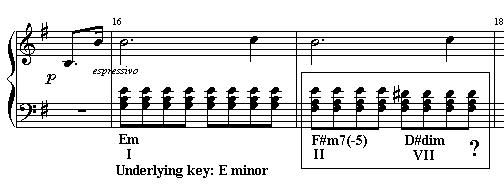

But there is another possibility. Eb is, of course, enharmonic with D#. Now, D# is a note in the E minor (both harmonic and melodic) scale. What happens if we change the Eb for D#?

Now we have a completely different (inverted) triad. If we restack the thirds, we get:

And if we look at the thirds from top to bottom we get minor – minor. This is the D# diminished triad. This triad can be generated from the VII degree of E major, from the II degree of C# minor (harmonic), from the VII degree of E minor (harmonic or melodic) and from the VI degree of F# minor (melodic). So, E minor can still be the underlying scale and the awkward intrusion of the G minor key disappears:

Finally there is another possibility. Rather than a D#dim triad, this could be an incomplete 7th chord. Adding a B to it, produces the B seventh chord. Which is of course the dominant seventh chord in the key of E minor:

You may ask at this point, “How am I supposed to know that I should add a B to make up a B7 chord?”. Besides the fact that it makes for a very neat progression, there is a huge hint in the melodic line: The B is right there occupying three quarters of the bar.

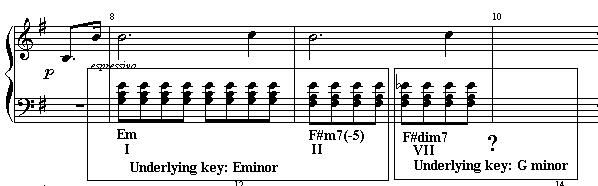

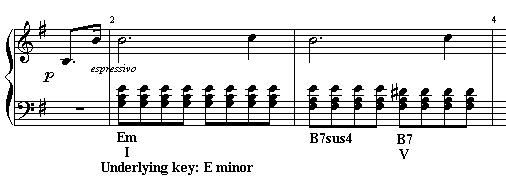

We now have the following progression for the first three bars:

Now this is a totally orthodox harmonic progression

, without any need to resort to weird chords and faraway progressions. In fact, So compelling is this train of thought, that in the Paderewski edition of the Chopin preludes, the editors (musicologists from the highest echelons of academia) did not hesitate in replacing Chopin’s original Eb for D#:

If one bothers to look at the notes provided at the end of the volume, the editors come clean:

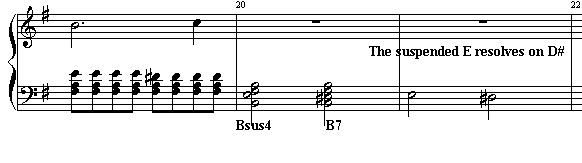

[…]we have changed the Eb of the original notation to D#. The chord in bar 2 is that of the dominant 7th in E minor (B-D#-F#-A, with the E suspended).Personally I am quite happy to go along with this. Yes, it makes a lot of sense that we have a progression that goes Em – B7sus4 – B7 (rather than Em – F#m7(-5) – D#dim).

However this does beg the question: This being the case, what possessed Chopin to write Eb instead of D#?

Maybe he did not know enough theory?

Maybe he was trying to point something that could not be properly said by using conventional harmonics?

Have a look at this opinion:

[…] Obviously Chopin wants us to feel only the tonic all through the first four measures. This results from the fact that he studiously avoids writing D sharp, instead of E-flat in measure 2: thus averting even the optical appearance of the V step in E minor; and the broad flow of the I tonic remains uninterrupted.(Heinrich Schenker – “Harmony” – Chicago University Press)

Although I am sympathetic to this point of view, it fails to truly convince me because at the end of the day, the Eb can be considered “tonic” only in the score (and we have to ignore the flat sign). In terms of sound – which is truly what matters - there is no mistaken that chord for anything but a dominant 7th. A very convincing experiment is simply to go to the piano and play each variant in turn:

So our harmonic analysis so far has brought us to this point (remember, this is all provisional, since what we discover later may require that we change our early opinions):

In any case, it is somewhat ironic that the editors of the much celebrated Paderewski edition let “harmonic analysis” considerations convince them to change Chopin’s original score. By doing that, they gained almost nothing - they just made it explicit what the harmonic progress was – and they may have lost something quite important that Chopin was trying to tell us – as we will see in due time. Eventually I will argue that the harmonic analysis we are presently undertaking is a dead end – there is a far more useful and revealing way to analyse this prelude. And yet it was precisely the considerations of an harmonic nature that led the editors to the change. There is a cautionary tale here.

Having said that, we do not yet know that harmonic analysis is a dead end. We are still exploring it, and we have just done three bars. One should now have a better idea on how to proceed with the next bars. Try your hand at the next bars now.

Best wishes,

Bernhard.